I stand on a chair to reach my grandmother’s birdcage. My dress and petticoat flip out in back, as I balance on my palms, my sturdy toddler legs straining toward the parakeet. The parakeet contemplates my nose poking between the bars. I want it to sing. It’s all I want of this place, this apartment which rattles like death when the El rushes by. I think how much I miss my own home. Unless the bird will sing.

Maybe it’s something that happened to me even before I was born. I started reaching out for the word music with my baby fists, if only to rush them like a bottle to my mouth: “Little Miss Muffet”; “See You Later, Alligator”; “A Fairy Went a-Marketing.” I recited and sang them repetitively—until my mother screamed at me to stop. Even then, I slipped under the bed covers and sang “My bonnie lies over the ocean, my bonnie lies over the sea.” My breath billowed up the sheet.

Maybe it’s something that happened to me even before I was born. I started reaching out for the word music with my baby fists, if only to rush them like a bottle to my mouth: “Little Miss Muffet”; “See You Later, Alligator”; “A Fairy Went a-Marketing.” I recited and sang them repetitively—until my mother screamed at me to stop. Even then, I slipped under the bed covers and sang “My bonnie lies over the ocean, my bonnie lies over the sea.” My breath billowed up the sheet.

Only a fifteen-year-old can make the leap from puppy love to bird lover. That’s what happened when I became fascinated with a boy with a bird’s name. My girlfriend and I followed him oh-so-subtly-and-cleverly in the halls, only running into him “by accident.” On the weekend I couldn’t wait for school to begin anew on Monday, so we went to the mall. Woolworth’s had a department with birds in birdcages. An arched cage so much like my grandmother’s parakeet cage held two lovebirds. I paid $9.99 for the lovers.

Only a fifteen-year-old can make the leap from puppy love to bird lover. That’s what happened when I became fascinated with a boy with a bird’s name. My girlfriend and I followed him oh-so-subtly-and-cleverly in the halls, only running into him “by accident.” On the weekend I couldn’t wait for school to begin anew on Monday, so we went to the mall. Woolworth’s had a department with birds in birdcages. An arched cage so much like my grandmother’s parakeet cage held two lovebirds. I paid $9.99 for the lovers.

When my husband and I got married in an ice storm, we drove from the hotel reception in a burgundy Marquise Brougham with a prayer on the dashboard. Songbirds flew after us into the dark. That’s the way I remember it.

I sat in Grandma’s old oak rocker, holding my baby son in my arms, murmuring:

Out of the cradle endlessly rocking,

Out of the mocking-bird’s throat, the musical shuttle,

Out of the Ninth-month midnight,

Over the sterile sands, and the fields beyond, where the child, leaving his bed, wander’d alone, bare-headed, barefoot

Whitman‘s poem managed something the others hadn’t been able to—it crept into my body, spreading out and occupying my flesh like a snakeskin it merely tolerated. I still can’t get rid of it. The poem and I battle inside like the gingham dog and the calico cat, but if it decided to leave, I’d be as empty as that snakeskin, discarded and colorless. It’s a poem about a he-bird who loves and loses the she-bird. Or it’s a poem about the curious boy who observes the bird and his troubles. But really it’s about a rocking like the surging of the sea and the hissing and whispering and all manner of delicious delicacies of words and rhythm.

When my parents put Grandma in the nursing home, she had to leave her parakeet behind. Not that yellow parakeet she had when I was a preschooler, but the green one she’d had since then. Dad brought the cage to our house and put it in the family room where the bird could watch TV. I kept changing the food and water, but the bird refused a single seed and died within a week.

When my parents put Grandma in the nursing home, she had to leave her parakeet behind. Not that yellow parakeet she had when I was a preschooler, but the green one she’d had since then. Dad brought the cage to our house and put it in the family room where the bird could watch TV. I kept changing the food and water, but the bird refused a single seed and died within a week.

Richard Siken told us wannabe poets never to write poems with birds in them. “It’s been done to death,” he said. I think he said that the bird as trope for poet was old after Whitman. Or maybe he said before Whitman. I went home and wrote a poem about Andersen’s Nightingale and the Chinese countryside and didn’t use the word bird. That’s what you call a writing constraint.

Richard Siken told us wannabe poets never to write poems with birds in them. “It’s been done to death,” he said. I think he said that the bird as trope for poet was old after Whitman. Or maybe he said before Whitman. I went home and wrote a poem about Andersen’s Nightingale and the Chinese countryside and didn’t use the word bird. That’s what you call a writing constraint.

We had such a problem with roof rats and teenagers. The latter we knew would eventually move out. My husband called in the pest control people for the former. The man the company sent shuffled and mumbled, so we let him go about his business. That afternoon my son ran into the house yelling his head off, and since he’s a mild-mannered young man, I scrambled to get to him. He led me out to the back steps where three baby birds hung on a glue trap like Jesus and the thieves. We poured a sort of holy kitchen oil to release them. One had already died and a second stilled the instant it rested in my palm. The third one regarded me with one black eye, vibrant as a drop of ink. We hustled it to the veterinarian where the techs hustled it out of our sight.

We had such a problem with roof rats and teenagers. The latter we knew would eventually move out. My husband called in the pest control people for the former. The man the company sent shuffled and mumbled, so we let him go about his business. That afternoon my son ran into the house yelling his head off, and since he’s a mild-mannered young man, I scrambled to get to him. He led me out to the back steps where three baby birds hung on a glue trap like Jesus and the thieves. We poured a sort of holy kitchen oil to release them. One had already died and a second stilled the instant it rested in my palm. The third one regarded me with one black eye, vibrant as a drop of ink. We hustled it to the veterinarian where the techs hustled it out of our sight.

My daughter writes songs that come out of her fully formed. I don’t know how anyone can do that, but then she sings them and her voice sounds like warm magma flowing. She sends me links to private songs on Myspace so I can listen before anyone else.

My daughter writes songs that come out of her fully formed. I don’t know how anyone can do that, but then she sings them and her voice sounds like warm magma flowing. She sends me links to private songs on Myspace so I can listen before anyone else.

Over ten years ago cats started showing up at our house, looking for food and, later, shelter. We only had a couple of dogs left. The birds had departed long before for their heaven. Now the cats outnumber the humans, and they think they have an equal vote. They vote that anything with a fast heart rate can be considered prey. So no more birds for our family.

Over ten years ago cats started showing up at our house, looking for food and, later, shelter. We only had a couple of dogs left. The birds had departed long before for their heaven. Now the cats outnumber the humans, and they think they have an equal vote. They vote that anything with a fast heart rate can be considered prey. So no more birds for our family.

This house in Arizona has a tile roof, and the pigeons think it’s a rocky hillside, like their homes before humankind. While pigeons have those pleasing round breasts and iridescent feathers like abalone, they excrete their body weight every day—and always from the eaves above my exterior doors. I asked my neighbor to stop feeding the birds, but she doesn’t speak to humans. We put up screens to stop them from roosting in the obvious places. But a stubborn contingent stay put, and from my fireplace I hear them cooing. My brown striped cat purrs on the hearth, in rhythm with the pigeon coos.

This house in Arizona has a tile roof, and the pigeons think it’s a rocky hillside, like their homes before humankind. While pigeons have those pleasing round breasts and iridescent feathers like abalone, they excrete their body weight every day—and always from the eaves above my exterior doors. I asked my neighbor to stop feeding the birds, but she doesn’t speak to humans. We put up screens to stop them from roosting in the obvious places. But a stubborn contingent stay put, and from my fireplace I hear them cooing. My brown striped cat purrs on the hearth, in rhythm with the pigeon coos.

A young pigeon dances on my patio, with his wings akimbo across his back, like a child stuck in a shirt he’s attempting to put on. Two adult pigeons watch from the roof. I put him in a brown bag and drive him to the pigeon lady. She has big man hands and examines him brusquely, but listens with her eyes closed, like a good doctor. She says, “I’ve never seen this before. It’s not a broken wing. He’s twisted his wings together across his back, like you twist a twisty on a bag.” She carefully and surely untwists his wings and puts them flat against his sides. “I’ll keep him for the winter and release him in the spring when he’s healthy.” I write a poem about the pigeon lady and through it she becomes a religious icon in my religion of one.

A young pigeon dances on my patio, with his wings akimbo across his back, like a child stuck in a shirt he’s attempting to put on. Two adult pigeons watch from the roof. I put him in a brown bag and drive him to the pigeon lady. She has big man hands and examines him brusquely, but listens with her eyes closed, like a good doctor. She says, “I’ve never seen this before. It’s not a broken wing. He’s twisted his wings together across his back, like you twist a twisty on a bag.” She carefully and surely untwists his wings and puts them flat against his sides. “I’ll keep him for the winter and release him in the spring when he’s healthy.” I write a poem about the pigeon lady and through it she becomes a religious icon in my religion of one.

In the summer, I bring her another pigeon. This one acts odd, walking around the yard, but only flying a few feet at a time. She tries, but can’t save this one. “He had an illness, and I don’t know what it was.” She wants my permission to do an autopsy. That’s the way she learns how to take care of the living pigeons. When I hang up the phone, I can see through the window that another pigeon resting at the edge of eaves is breathing rhythmically as its body empties and fills and empties and fills in an unbroken pattern.

In the summer, I bring her another pigeon. This one acts odd, walking around the yard, but only flying a few feet at a time. She tries, but can’t save this one. “He had an illness, and I don’t know what it was.” She wants my permission to do an autopsy. That’s the way she learns how to take care of the living pigeons. When I hang up the phone, I can see through the window that another pigeon resting at the edge of eaves is breathing rhythmically as its body empties and fills and empties and fills in an unbroken pattern.

My grandmother outlived her parakeet in the nursing home for a year. I told my parents that if she had had the parakeet in her room, she and the parakeet would both have lived longer, but they explained that she died of uremia from renal failure. “The bird died because it didn’t eat, Luanne,” my mother said. “Stop trying to connect things that are not related.”

My grandmother outlived her parakeet in the nursing home for a year. I told my parents that if she had had the parakeet in her room, she and the parakeet would both have lived longer, but they explained that she died of uremia from renal failure. “The bird died because it didn’t eat, Luanne,” my mother said. “Stop trying to connect things that are not related.”

I have only one word….Amazing!!!

Darcy, thank you so much! I’m so glad you liked it!

you are my blogging kindred spirit! i love your posts. old pictures, anecdotes, literary references, and all.

Sarah, that’s what I was thinking! Love your gravatar pic!

All I can say is: beautiful.

That makes me so happy that you liked it, Lisa :).

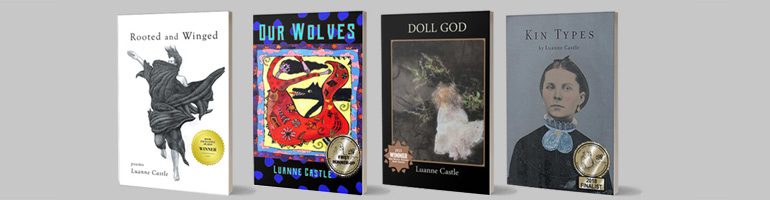

I loved this intersection between prose and poetry, this “all I know about birds” –> which is a lot. I loved the photo of toddler Luanne and the bird. What superb writing.

Wilma, that means so much for to me! Thank you so much for being such a loyal reader.

Artistic, descriptive, beautiful! Loved reading this.

Carla, thank you so much! I hope it appealed to your poet’s heart and mind.

This is an amazing story, beautifully written with such love and feeling. I haven’t the words to tell you how much I enjoyed it or how it spoke to me. This is so special, I’ll be reading it again And again. Thank you for it.

Oldsunbird, that makes me so happy that this piece spoke to you. Thank you so much for letting me know!!

Reblogged this on Writer Site and commented:

Today’s reblog is about an influence on my life–and a prevailing metaphor.

<3

Thanks for reading, Sue!

Luanne

wow! this is so lovely, i sit and sigh and take it in, read it again. beautifully written. Whitman spread all over my bones also, like moss. i can’t even tell which parts of this i like most, although those last lines keep tugging at my chest.

Oh, Gwendolyn, I’m so touched that you enjoyed this piece. Thank you for letting me know about the last lines. It means a lot. And I love that Whitman spread like moss over your bones :)!!

Luanne

Just beautiful, Luanne……reminds me of childhood…..I lost a lot of my memories of childhood with the brain surgery. I love your blog because it helps me remember…..Jill

Jill, I’m so glad that my stories help you to remember. And I”m so sorry that you have lost so many memories. xo Luanne

P.S. I just discovered that I had a lot of spam in here and there were posts you made that made their way into the spam folder for some reasons! I apologize for not responding to them!!!

Beautiful how you connected all the little episodes and each one of them is a gem in itself.

Lena, thank you so much for your lovely comment and for following my blog.